Randolpho Lamonier in conversation with Maxwell Alexandre

[01 de abril de 2021]

Raphael Fonseca: Based on some of the questions I came up with, one thing that has been on my mind is what unites us? None of us come from a family background of visual arts. I was born and raised in Taquara, Jacarepaguá, in Rio de Janeiro and I am the first person in my family to have gone to University.

Maxwell, I know that you attended PUC-Rio (Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro) and I know Randolpho went to UFMG (Federal University of Minas Gerais). There is something that I think is interesting in both of your works. Randolpho thinks about his relationship with Contagem, which is a town near Belo Horizonte, while Maxwell focuses more on his roots from the Rochinha. I am going to begin by first asking Randolpho how he manifests and transforms the theme of his birthplace, Contagem, in his practice.

Randolpho Lamonier: It’s hard to answer this question because the subject, themes and discussions that are present in my work are very fluid.

When I started attending UFMG, around 2012, is when I first began to look back and reflect on my childhood in Contagem. Because of the four-hour commute by bus, I had to move away and ended-up relocating to Belo Horizonte. However, only once moving to Belo Horizonte did I begin to notice details about suburban life. My colleagues changed, my social circle changed, and I began to get a glimpse of this world that I was stepping into, the art world. I started to think more about the meaning of authority. I felt very weird in the beginning, but ended up connecting with friends and colleagues who also identified with these “weird” feelings. For example, Dayane Tropicaos is one of those people. We lived in the same neighborhood and ended up meeting in college.

Only after having moved away from Contagem to pursue my studies in Belo Horizonte, did I begin to feel the need to go back to revisit my hometown, but this time from the point of view of a foreigner.

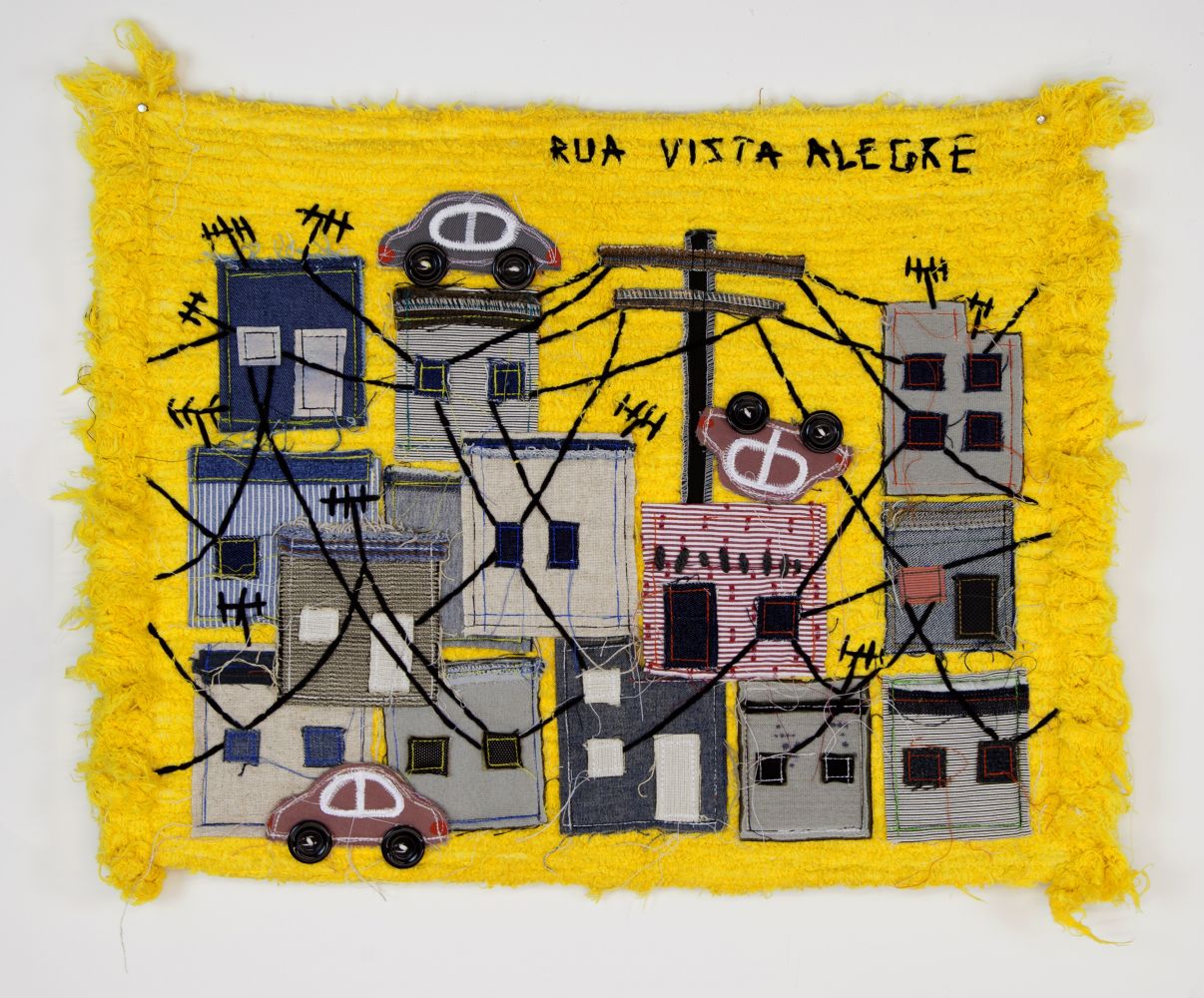

I began to pick up things as metaphors. For example, the industrial aspect of the city says a lot about my personal experience there. My whole family worked in a factory, especially my mother who has done so her entire life. There is hardship in such places, which is why I immediately connected with the reality of this environment. So, I started visiting some abandoned places such as factories, railroad tracks, abandoned parks and I eventually started drifting away.

Contagem is all connected by railroad tracks that are used for the transportation of iron ore. I started combining what my city had to offer because of this. I started working with fire and mainly creating drawings on the floor.

A specific thought I had during this time was about my relationship with work. In a metaphoric sense, the harsh side of life from a political and anthropological view. I began to explore and study how my family’s life at work manifested into the dynamics of our relationship.

Now, I often try to go back to Contagem, as my whole family lives there and the majority of my friends. All my memories and issues, regarding work, originate from this place. Contagem is a place that I will always keep going back to.

RF: Perfect! Maxwell, how is your relationship with the Rochinha? I think it’s quite different from Randolpho’s case. You mentioned in your interview for the PIPA Prize that you never moved away and keep living there till this day.

Maxwell Alexandre: Exactly! There was always a mental distance, never a physical one. I’ve never left the Rochinha, I’ve been living here for the last thirty years since enrolling in University in 2011 to study graphic design and visual arts. I encountered the concept of contemporary art later in a course I took with Eduardo Berliner, and this is when my life changed. This is a field in which I could find myself, with graphic design there were many sophisticated issues that I could work with. I didn’t have a lot of financial resources, so I had to improvise a lot and I felt comfortable doing so through art.

While attending university, I was still very rooted in the evangelical religion and I was often made fun of for that. I started seeing everything as a church, such as my university, and what I mean by church is the structure of it. I started learning more about other religions and their stories. The more I learned, the farther away I felt from Jesus. I felt a divide taking place. I learned the name of Jesus doesn’t have any power, but being an artist is a place of reverence. For example, an atheist that doesn’t believe in anything would look to a piece of art in reverence and cry.

Every time I returned to the slum; nobody would care if I was an artist. I would collect things in the streets, as I often saw the potential of what it could become, once integrated them into my artwork. I had to preserve the name of Jesus in the slum. These where the two worlds I was living in. I didn’t realize that at that time, I had to take a step back to be able to understand the difference of these two worlds, which now I believe I do.

Faith, for example, is an important aspect of my life. Faith and creativity to me are rooted in the same foundation.

Attending an expensive university and living among a ‘class A’ environment, caused my behavior, vocabulary, and style to change. I was mentally living in this sperate world, and physically living in the slums.

I trained myself to view the world through beauty, history and visual communication. Debates that focused on the topic of minorities started to capture my interest. The fact that I am Black, as well as other concerns and frustrations, is what made me brake away from the ‘class A’ system. I came back to my world, the slum, and decided to stay in this world.

RF: Let me ask another question starting with Randolpho. Both of you deal with very fragile materials in different ways. Randolpho how do you deal with this aspect of fragility within your work?

RL: Before working as an artist, I was working in theater as an actor, and this is where I gained the majority of my experiences. No one in my family believed that this could be a profession. I initially started taking a theater workshop in Contagem and, once I moved to Belo Horizonte, I pursued my university studies as a theater major, until I ended up working in an office job. I was 18 years old when I joined this company, so the experience of working with my colleagues greatly impacted me. One person who influenced me the most was my aunt. She was a poet who worked a lot with her hands, and you can see her influence in my artwork.

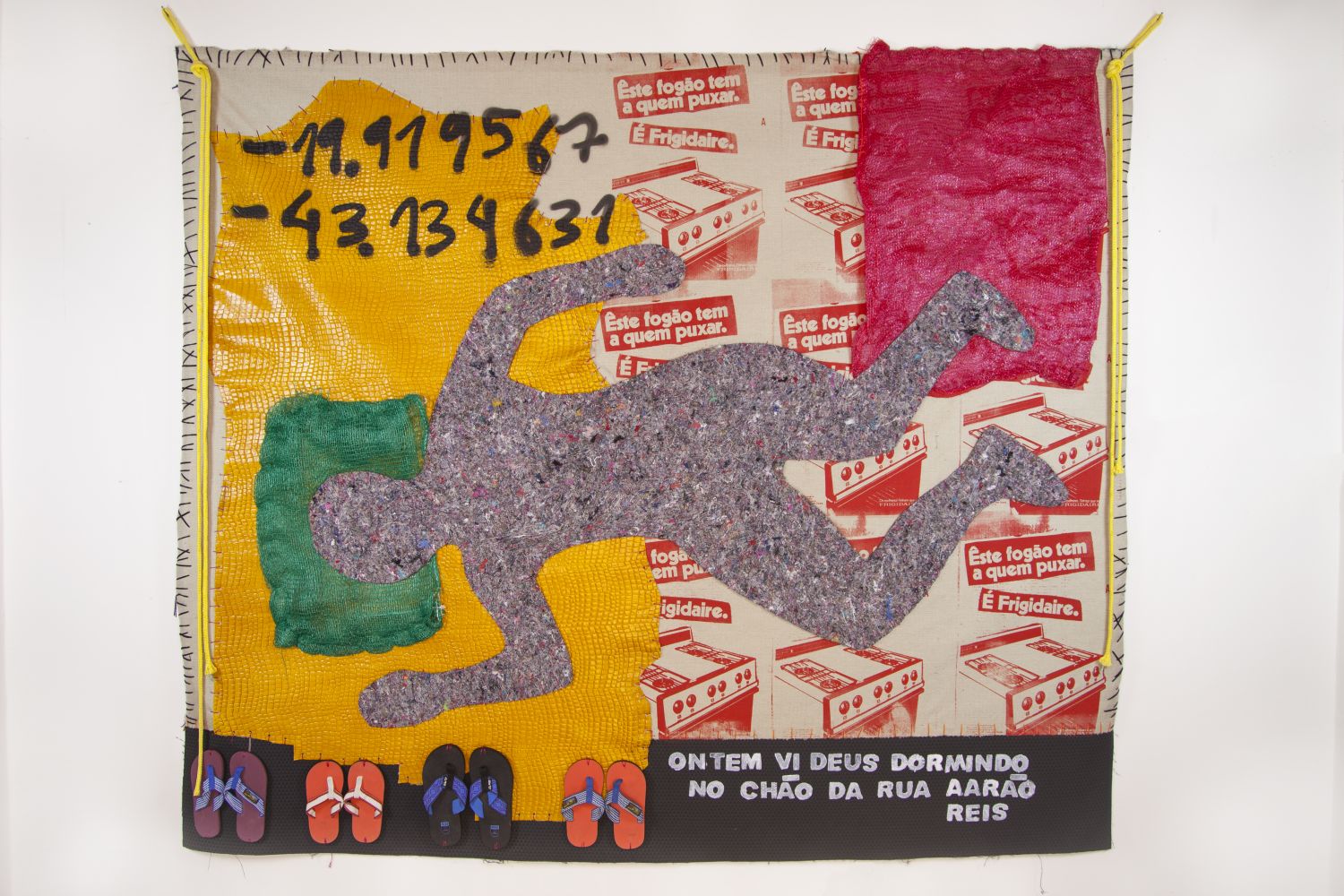

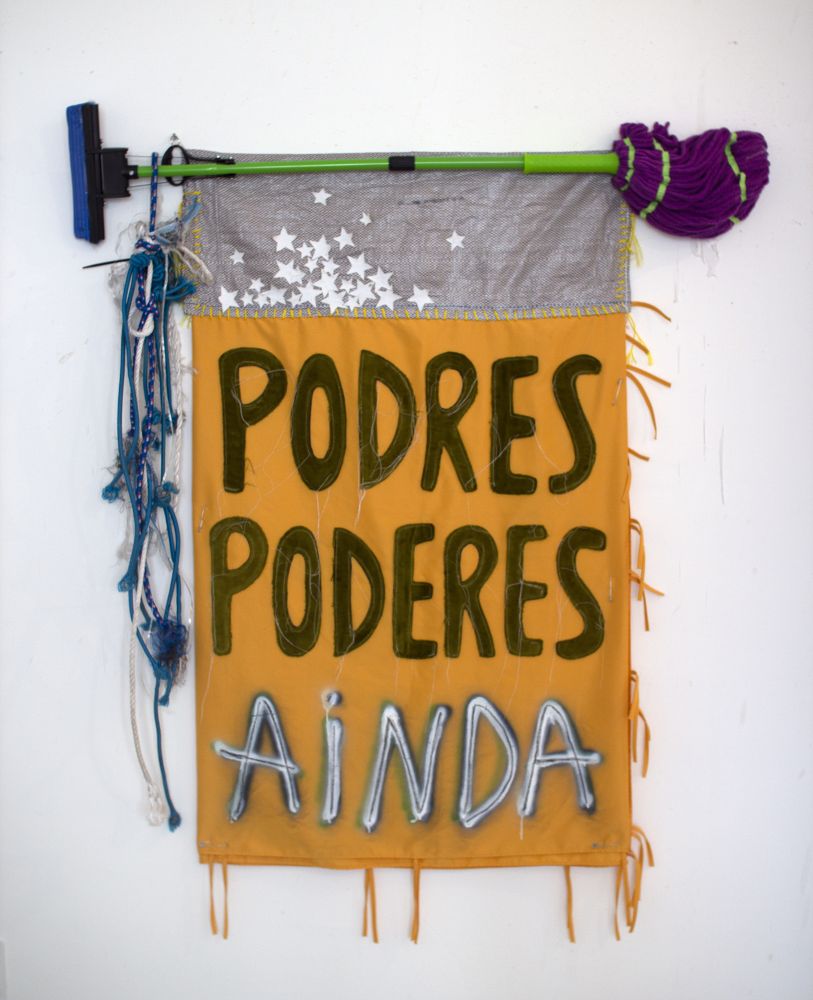

I work a lot with the idea of excess and often collect a lot of the materials directly from the streets, as I cannot afford much. When it comes to working with textiles, it is very important for me to work with used materials. In the past, there have been times where I wanted to work but had no money at all. Sometimes I had to use pieces of my clothes as material. Nowadays, this has become a part of my work. I try to change the meaning of objects through my work. For example, I have used kitchen supplies in different contexts.

My relationship with art is related to my experience in the theater industry. I work a lot with my body, as I move around a lot when I work; sitting still is hard for me. When there is an exhibition and there is a piece of art that comes out from the wall, or is hanging from the ceiling, I want the people to see it through my perspective.

RF: Maxwell, tell us more about how you plan your exhibitions.

RL: I just want to comment really quickly about your exhibition named “Windows”, which I was very impressed with and touched by.

MA: Thank you! Once I start a project, it’s as if I become a part of it. My paintings are like graphics, they are manifestations of writing. What I try to do in my work is not to think or follow rules, but rather follow my instincts.” My art is like a religion, the fact that I use black wax and black hair dye, has become a political fact. The experiences I have, end up being connected to one another. With the brown paper, I was told to use small sizes, as it would have been easier to sell, but what interested me was to work in a bigger dimension. The fragility of the brown paper and the blackness of the wax made it very poetic for me.

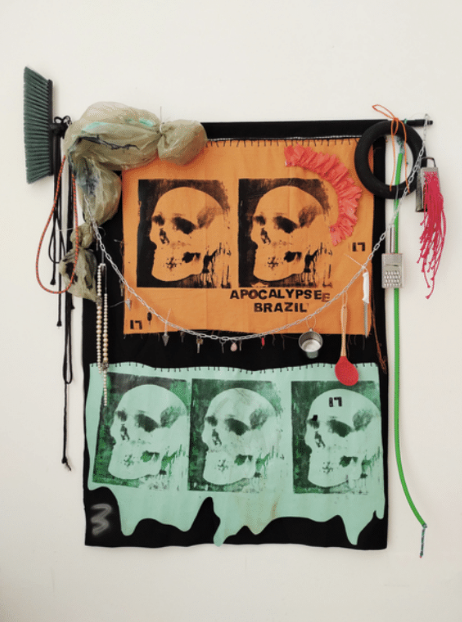

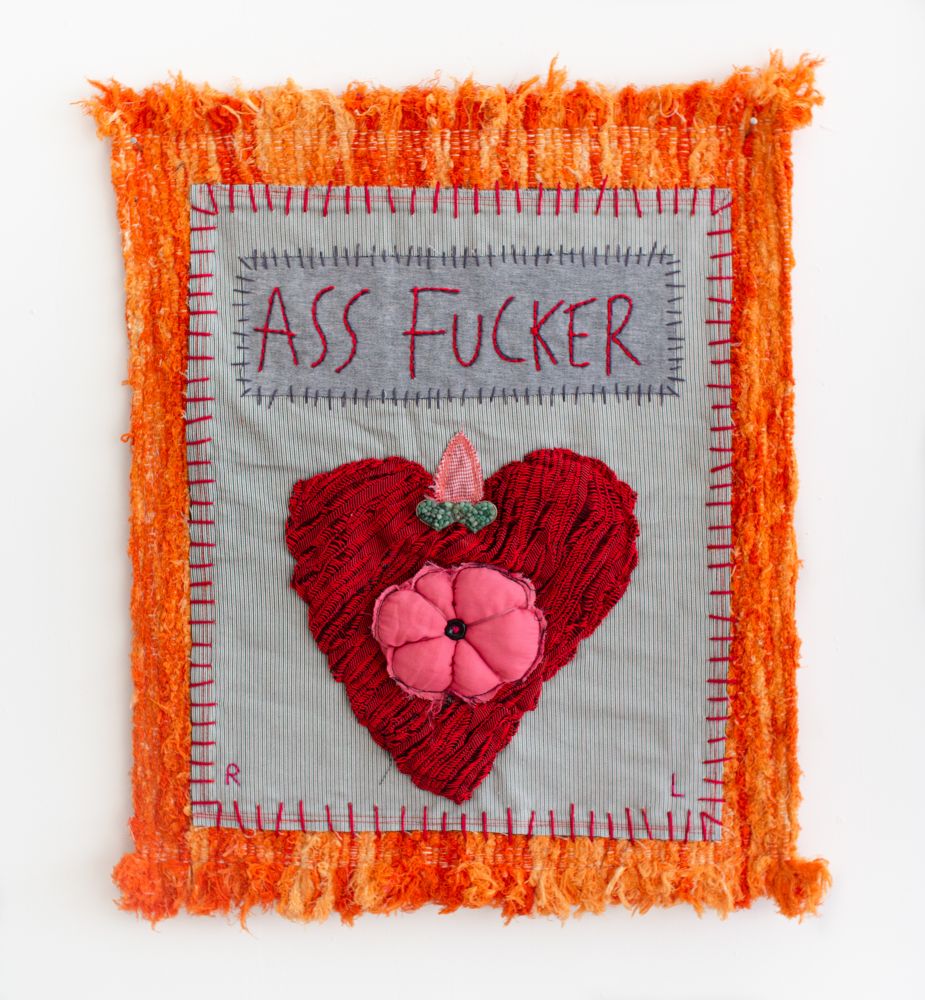

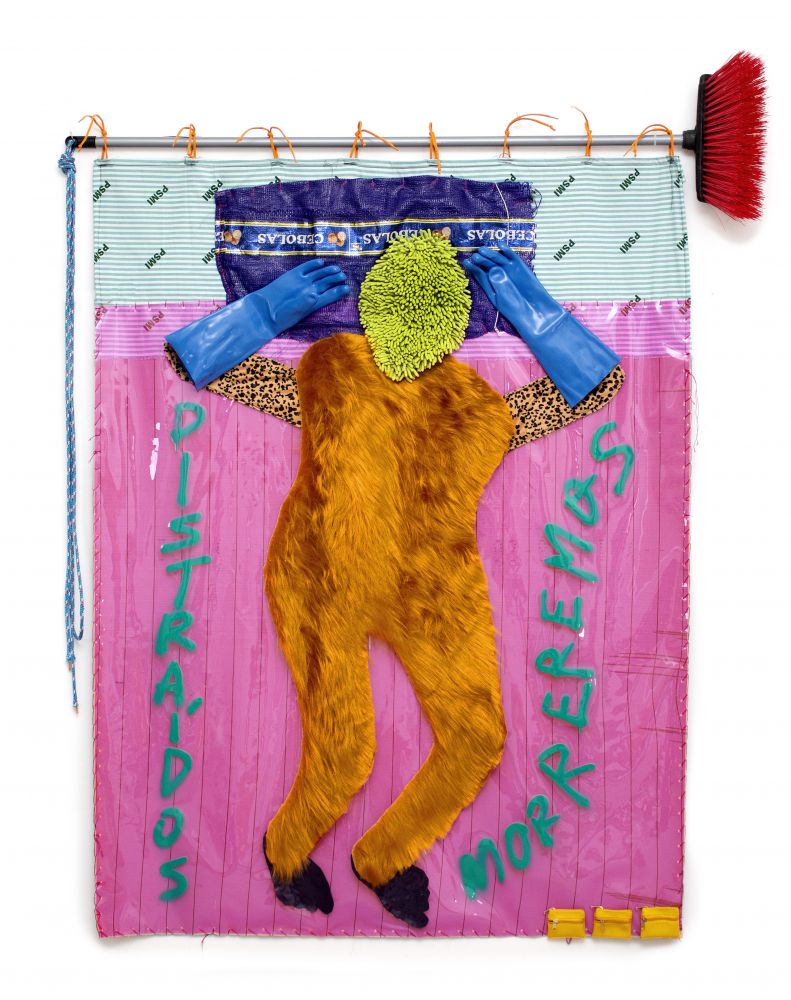

RF: I wanted to ask one last question for the both of you. Randolpho, you recently sent pictures of your artwork from your exhibition, “My Kind Of Dirty”. One set of images showed the Brazilian president wearing a facemask, while the other ones were a series of serigraphs of skulls.

I wanted to ask the both of you, and get your opinion on the notion of using historic and political events in art. What is it like combining different techniques and materials?

RL: I have used some political and historical images before in some videos and, recently, they are reappearing in my work, which is not intentional. The images that are being used in my work come from media, newspapers, etc. This collection of serigraphs I worked on was my very first one. I went back and forth many times about reproducing the face of our current president in Brazil as I thought that image was very symbolic.

Regarding different types of media, it’s difficult for me to comment because of my formation in visual arts and its innateness. The use of video art became an important part of my life, stemming from my childhood, as my uncle owned a film-making company. I had many part time jobs growing up, which, in one way or another, influenced my work. Because of all the different jobs I’ve had, I don’t see any difference in the creation process which involves different types of formats. For example, video, photography, etc.

MA: In my case, painting is the type of media that has given me the fastest result in terms of recognition. The fact that a painting is so unique makes it more relevant than other types of media. The painter, when he paints, feels he has the power to tell his story.

During my time at University, I would often work with Keith Haring’s drawings and because of its complexity, I never had any difficulties when it came to copying images or pictures. I did this because I felt the urgency and need to tell stories in the street and to be able to educate the slum through my artwork. I would look at these drawings as if they were a very simple alphabet, to be used as letters to write the story that I wanted.

Ultimately, I developed something that is mine and original, although I look at art as something that is universal. I think of art as a software or a research tool that may be used freely by everyone.

RL: Sometimes my work portrays the message of hope and, at other times, of despair. To me, art is a significant part of my life, as I tend to view my artwork as a means of receiving answers about my life and the world around me. When I look at myself, I see confusion, just as I do when I look around me.

I consider myself to be a very hopeful person in the sense that something positive can always happen. I project my hopes and faith in my work.

RF: How do you feel being an artist in Brazil during this scary political era?

RL: I now feel very challenged as an artist. I ask myself, "what is my work and time asking of me as an artist?”. In my opinion, it is very important to use your platform so that your work can have a voice of its own. I feel very anguished with the current situation here in Brazil, and this moment of crisis we are experiencing only makes me want to push forward to reach my goals.

(conversa relativa à exposição “My kind of dirty”, de Randolpho Lamonier, na Fort Gansevoort, em Nova Iorque, Estados Unidos, entre 01 de abril e 15 de maio de 2021)