The sun teaches us that history is not everything

[25 de março de 2018]

An introduction

The year was 2017.

The president of the United States of America, Donald Trump, declared that he wishes to build a wall that divides his country from Mexico.

The Singapore Biennale titled “An atlas of mirrors” gathered works essentially about borders and geography.

Hong Kong already had 20 years that went back to the Chinese administration after its long period under the British power.

The Documenta was titled “Universes in universe” and had one research area dedicated to the “global South” named “South: a state of mind”.

Part of the Brazilian population went to the streets in public manifestations against the left-wing party. People wore green and yellow in a clear reference to the nationalistic manifestations did during the military dictatorship period.

The Getty Foundation, in Los Angeles, promoted the event “Pacific Standard Time”, where institutions of the city received dozens of exhibitions that stablish dialogues between the USA and the art made in different places of Latin America.

The movie “The act of killing”, a re-enactment with the responsible for mass killings of communists in Indonesia during the dictatorial government of Suharto, had its fifth anniversary of release.

The Museum of the Chinese Colony (Museo de la Colonia China) in Guatemala opened in memory of the migration from China to Central America during the 20th century.

Rogerio Duterte, president of the Philippines, admitted the murder of hundreds of people supposedly involved in drug dealing in the islands due to the maintenance of the national order.

The singer M.I.A., born in London and with origin from Sri Lanka, asked herself in a song: “Borders (what’s up with that?) / Politics (what’s up with that?) / Police shots (what’s up with that?) / Identities (what’s up with that?)”.

Tropicalities

The words above were written as an introduction to an advanced version of the exhibition project "The sun teaches us that history is not everything", thought for the Osage Art Foundation since 2016. All from 2017, these notes on facts and political perspectives of different places of the globe were written in the heat of their events. Due to the realization of the exhibition in 2018 and the subsequent publication of a catalogue, I adapted the verbs of the sentences to the past. Much has happened in international politics since then as a result of this list of news.

From the point of view of the country where I was born and live, Brazil, those street demonstrations with people wearing green-and-yellow shirts and praising our military dictatorship period (1964-1985) took, last month, to the presidential victory of Jair Bolsonaro, an extreme right-wing, military and partisan supporter of positions that go against democratically acquired human rights over the last three decades in the country. The motto of his political campaign was "Brazil above everything, God above all," which brought in itself - consciously or not - both a religious takeover contrary to the Brazilian secular state (in our constitution of 1988), and a ghost of the Nazi motto "Deutschland über alles", "Germany above all".

What drives this discourse and all those contained in the introduction is a strong nationalism anchored in political stances already seen in totalitarian political systems. It is difficult not to remember some publications in the field of historical studies that analyse other moments in which the semantic field of words like migration, borders, nation, invasion, escape, refuge and identity were discursively triggered for the same purpose. I refer to the book by Benedict Anderson, "Imagined Communities" (1983), a key text on the analysis of mechanisms for the creation of new nationalisms.

The relation between the present and the past was always articulated by different political strategies that wanted to forge new geographical identities. A specialist in the Southeast Asia, Anderson demonstrates in this book how the nationalistic fictions were essential to define borders, stablish commercial agreements and to justify the bad relationship between different pairs. More than mentally imagine a specific community, the agents of culture created images that aimed the masses and that could freeze essential convictions to the idea of nation. It’s nationalism, this notion of collective belonging that exists since Antiquity that, for example, makes Donald Trump willing to “make America great again” or that justifies the murder of masses in the Philippines recently. On the other side, the attempts to complexify this concept take to curatorial proposals like Pacific Standard Time and to the poetry of an artist like M.I.A.

The starting point for this curatorial project comes precisely from another moment of Brazilian nationalism in the nineteenth century, as opposed to the immigration of non-Western peoples. In 1850, the Eusebio de Queiroz Law prohibited the international trade of enslaved black people who arrived in the country through the Atlantic Ocean. The whole history of the region was based on black slavery as a labour force - from plantations to the white family private sphere. Once the law was published, alternatives to the workers had to be drawn.

One was the possibility of the arrival of Chinese workers, something already seen in the colonies of other European empires throughout the Caribbean. Cultural differences and the fear of otherness led to a Chamber of Deputies session full of racist speeches based on recurrent eugenic theories in the nineteenth century.[1] In June 1890, the Brazilian government created a law prohibiting the entry of Asians and free Africans into Brazil expressing the understanding that only the European labour force would be able to whiten Brazilian society. Here is a bit of the history of racism in Brazil.[2]

Learning about these facts on the history of immigration in Brazil caught my attention during my doctoral studies. In a common sense, whenever we refer to the Asian presence in Brazilian culture, we remember the Japanese immigration that happened systematically since 1908, with official support from the Japanese government.[3] Predatory narratives - and even the histories of the Japanese in the country - tend to be eclipsed by other Brazilian racial narratives that quote Karl von Martius's famous text on the "theory of the three races."

The ethnic constitution in Brazil, according to the author, would have occurred from the encounter between indigenous peoples, enslaved black peoples and Europeans who colonized the territory, especially the Portuguese.[4] It is an argument made by a nineteenth-century German scientist who also owes the notion of eugenics and summarizes both racial diversity and violent conflicts from the idea of mixing. Certainly, we should not try to find in this argumentation – in an anachronic way – the critical gaze that the present allows us but it calls my attention that the intellectual production in the country sometimes still uses his theories more than a century and a half later.

These readings led me to a question: what is the place of the Asian peoples in the narratives about the identity and history of Brazil? Later, due to a series of curatorial research trips that I conducted through Central America and the Caribbean[5], the questioning was extended from the Brazilian territory to this gigantic region, which we call Latin America. Japanese immigration waves were important not only in Brazil, but also in Peru and Mexico. Similarly, Chinese presence in Latin America was most felt in countries such as Panama, Peru, Cuba, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic. These stories, however, are told in a supporting manner in the official narratives of these countries; they are generally absent from History classes in basic education and still suffer prejudices like those pronounced during the nineteenth century.

Gradually I met Latin American artists of Chinese and Japanese ancestry based in countries like Brazil, Costa Rica, Peru, Guatemala, Argentina and Mexico.[6] The search for these poetics made me to know other curatorial projects also interested in this intersection between Asian and Latin American cultures. It is curious to note, however, that many exhibitions bring together descendants of specific nations - such as projects on Japanese artists in Brazil, for example - but do not dwell on those artists who effectively construct and deconstruct notions of history, identity, and nationalism in their poetic.[7] I decided, therefore, to focus my attention on those artists who, in addition to their genealogy, somehow are interested in questioning those relations that led to a non-identity belonging in the hegemonic narratives of their own countries.

In dialogue with Osage Art Foudation, I learned about the Regional Perspectives program and the exhibition previously curated by Anca Verona Mihulet and Patrick Flores, "South by Southeast". As the name suggests, the program supports curatorial projects that put the production of art in different geographies in a critical perspective, always having as one of them the Asian continent. Mihulet and Flores, for example, connected artists from Southeast Asia with others from Eastern Europe and sought points of contact and dissimilarity. Having such research in development in Latin America, what connections could be made with artists based in this extensive region called Asia? The answer, again, came by looking at the past.

The histories of Latin America, Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia have a key concept in common: colonialism.[8] Just as South America and Central America were colonized by Spain and Portugal, Hong Kong was a British colony, Macao a Portuguese territory, and the only country in Southeast Asia that was not colonized was Thailand. According to Milton Osborne[9], Southeast Asia is a region that is often only considered during and after its colonization, but each of its present countries already had millennial cultures that sometimes exceeded in population numbers places seen as central to Western culture. Even historical studies, therefore, sometimes use an Orientalism that reduces the region to common historical factors and doesn’t throw light on its specificities – just like the creation of an idea of "Southeast Asia".

When I researched the Asian Latin American artists, I was looking for narratives of immigration and diaspora; when I started to research artists from different points in Southeast Asia, I found narratives that looked after colonialism. In this way, I thought that this would create a peculiar curatorial point of contact between Latin America and Asia based not on the same starting point, but rather along an intersection of different groups of interest.

Looking for a deepness of the research to be deep based not only on reading, but on the experience in loco, it was essential to travel to some countries of the region. In January 2017 I made a trip of about a month that began by Hong Kong and Macau, and later landed in Singapore, Indonesia (Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta) and Philippines (Manila). All my readings about the histories of these places, my contact with the artists and their poetics gained new meaning after experiencing cities as different as Manila (Philippines) and Singapore (city-state). It was essential to visit not only art museums, but especially the museums of national History - how do these nations narrate their own past? Which of these countries have contemporary art museums and fine art collections? What is the interest of their private collectors of art? The economic, urban, and especially the differences in institutions and infrastructure for the visual arts in these countries quickly call our attention and allow us to easily doubt any discourse that aims to homogenize the artistic practices of Southeast Asia.

The same can be said about the history of territories as close and small spatially as Hong Kong and Macao. In the same way that its historical settlers operated in a different way, the way in which both countries are administered by China today is different in different spheres. Not even when we refer to "China" can we pursue that same cultural, linguistic and political unity.

It was essential to conclude that the use of an expression like “Southeast Asian art” is closer to fiction than fact. In the same way, other expressions commonly used in the contemporary art field like “Latin American art”, “African art”, “Chinese art” and “Arab art” shows how the subjection of the artistic phenomenon to a geography can help studies but can quickly become a problem. How to put the production of art in places with so different histories like Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia in the same box? How to equate the Japanese communities in Brazil, Peru and Mexico? The answer is simple: it is not possible to do it fairly. We can create areas of dialogue, but words can’t never resume the complexity of art, image and culture.

Even though we are on different sides of the globe, we are both part of the area between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, with most of the countries here mentioned being below the Equator. In addition to our climatic and colonial similarities, we are part of the so-called Global South, an expression that is increasingly in vogue in contemporary cultural studies and, consequently, in the thinking of contemporary art. Cuatehmóc Medina, an experienced Mexican curator who has acted within its sphere, wrote about this question precisely:

After two decades of irruption of the periphery art alliance, and after the geographical and historical recomposition of the narrative of the history of modern and contemporary art, what new centrifugal forms emerge from the culture below the Equator line? What promises are contained in the task of re-evaluating the cultural genealogies of the South: the memory of dictatorships at the same time as the possible tropicalizations of conceptualism? What new fissures open in the illusion of absolute closeness from what is still distance? To what extent can artistic practice, globalized or locally effective, still be attributed to the decolonization project?[10]

The South - or, as I prefer to say, the tropics - has much to learn from itself.[11]There are many notions of tropic and tropicality within this vast area which we call tropical. Brazilian tropicality is not the same as that of Philippine tropicality - but the fact that it was the result of the Portuguese invasion and the second of the Spanish invasion, both Iberian nations, made me feel a certain sense of home in Manila that I could not feel anywhere else from the places I visited in Southeast Asia. Traveling is necessary and establishing crossings - as proposed by this curatorship - as well. What we cannot lose of mind, however, is that the "Global South" is only a starting point that will only be valuable if we continue to doubt its classificatory condition and realize that it is in the difference that we are constituted.

Albert Camus and the sun

The title from this project comes from a quote and adaptation of a paragraph originally published by Albert Camus. Born in 1913, in Algeria, Camus became one of the biggest voices in the French literature in the first half of the 20th century. Born in a moment where Algeria still was a French colony, Camus lived in Paris and followed part of the process of the Algerian independence, only finished in 1962, two years after his death. This information contributes to comprehend his poetic insistence around the sensation of being a “foreigner” (title of this most famous book published in 1942). We could affirm then that the author was fruit of the encounter of colonial and post-colonial reflections around his own time.

In 1937, only with 22 years, Camus published his second book in Algeria, “Betwixt and between”. The book has five short stories about people in situations of travelling, strangeness and solitude. Twenty years later, in 1958, already in France, Camus republishes the book and writes a preface. This text has a strong autobiographical tone, where he reflects about his childhood in Algeria and points the differences he found living later in France. Remembering of his poor life and his experience that was closer to the landscape than to material world, Camus writes the following periods: “To correct my natural indifference, I was put in the midway between the misery and the sun. The misery prohibited me to believe that everything goes well under the sun and in history; the sun taught me that history isn’t everything. To change the life, yes, but not the world in which I did my divinity”.[12]

Misery, the colonial condition of his poor childhood in Algeria, couldn’t be apprehended separated from the sun, the landscape condition of his geographical localization. Between there and here, instead of looking for an official History to justify his human condition, Camus opted for the power of fiction and wrote episodic stories. In the quote, he learned that not everything goes well under the sun but, at the same time, the obsession with a literal discourse from a historian also wouldn’t make sense when confronted with the monumentality of the sun.

This text by Camus met the central interest of this curatorial project: gather artists that have interest in the elements of the present that touch historical aspects of the formation of national identities. While part of the artists refers to the state of being an “Asian” in places where the nationalistic discourses push toward the affirmation of “Latinity”, others observe how in the present it is still possible to see elements that came from the colonization desired by the European imperialism. In other words, it is possible to affirm that the artists that take part in this exhibition – each own in its own way – are “artists-historians”[13].

However, just like Camus affirms that he is closer to stories than to one History, this show gathers artworks that take the same proposition. We – me and the artists – were looking for a more poetic, less literal and more experimental look to facts and images. We understood that the word “History” as a series of elements that can be folded, forgotten, reconstituted and juxtaposed for an artist to reach a formal result capable to invite the public to think about the present and political conflicts we deal with.

It is because of this curatorial interest that the quote to Camus was adapted. Instead of reading “The sun taught me that history isn’t everything”, I opted for “The sun teaches us that history is not everything”. We take off the verb in the past and put it in the present; we extract the verb from the first person of singular and write in the plural. The learning is made in the contemporaneity and it is not only about one person but about the dialogues with the public. The sun is always present – the star that makes Latin America globally known by its tropical climate to the Eurocentric thought is the same that gives light to the Asian tropics and made orientalism possible. Even with so different narratives, we continue under the same sun.

Ways to fold history

Twenty-five artists occupied the Osage Art Foundation exhibition space in "The sun teaches us that history is not everything". The large size of the floor that the institution occupies in Kwun Tong resembles a corridor and, for the exhibition design, we chose not to create any great artificial intervention. One area of the exhibition was more dedicated to installation, object and wall works in which the lighting became essential. The other, more dedicated to video and needed a darker environment. Both balconies were also occupied with site specific interventions.

No geographical or thematic division has been established between artists; the public was invited to go through the space and perceive the dialogue between works placed side by side. The encounter between Asian and Latin American artists was thus suggested - without initial separation and without creating new boundaries between "we" and "them". A watchful eye would see lines of force in the display that were beyond the geographical belongings. There are many ways of doubling historical narratives in contemporary times, and it seems to me that this was the greatest contribution made by the project: to bring this diversity to the public and to realize that daily, in our minor acts, we are always reliving or exorcising past. As our title says, "history is not everything", that is, it is a starting point that invites us to observe elements that escape its desire to rationalize and organize the world.

I would like to point out some of these dialogic ways of acting in the field of visual arts looking at the past perceived through the approach of some artists of the exhibition.

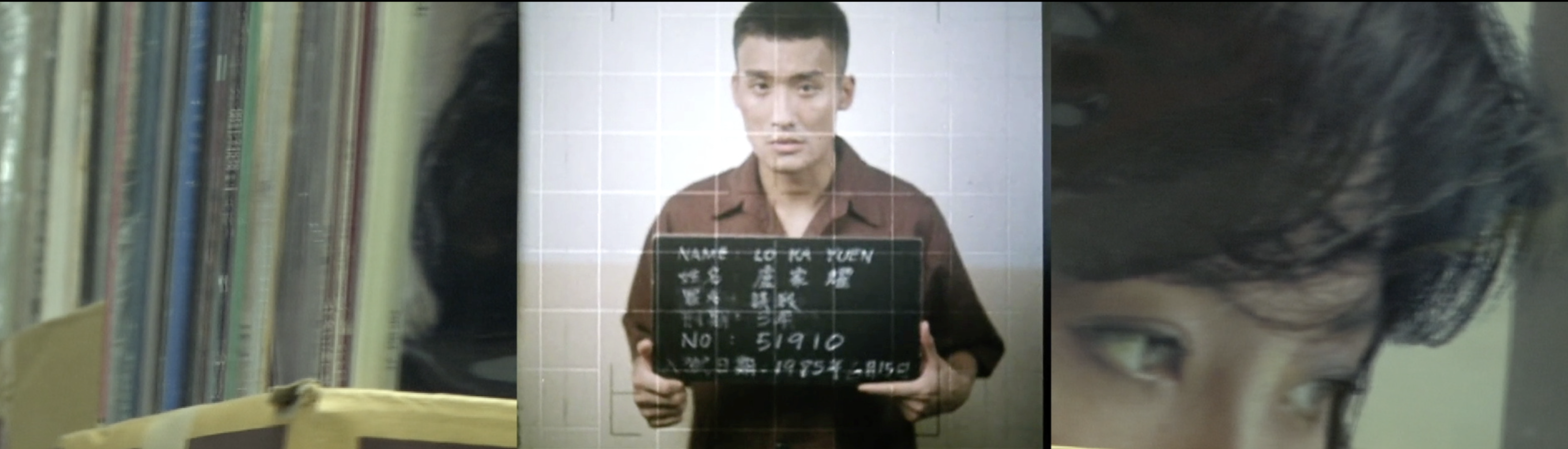

* archive images - many of the guest artists work directly with archives.[14] Rather than altering the initially researched images, they quote integrally their sources and insert them into new narrative structures. This is particularly visible since they all work with technical images - photography and audio-visual. Their gaze seems more focused on the re-reading of great historical narratives. While André Terayama used a photograph of the great Japanese photographer Haruo Ohara, Yudi Rafael developed a work based on a survey of the visual culture developed in Brazil and the United States about the descendants of Asians. Nguyen Trinh Thi and Linda Lai built works made from excerpts from other films that said a lot about the collective imagination about Vietnam and Hong Kong. Archives, film libraries, art collections and libraries are some of the spaces explored by this line of research.

* tradition, appropriation and recoding - in a parallel but different way, some artists present in the project did not only quote a specific image or formal element but subverted it through interventions that tend to say a lot about a political statement and about the weight of updating the past in the present.[15] A good example is the way Norberto Roldan juxtaposes three-dimensional sculptures with a religious aspect alongside flags that refer to political conflicts in the Philippines. There are many layers of association there, as well as Kent Chan's proposition, a video installation around the first exhibition of Singaporean art outside Singapore, in London. The letters are on the table and the artist rewrites the past in the way that interests him. Similarly, focusing on sound and its absence, Mark Salvatus calls popular musical groups from the Philippines and Melati Suryodarmo uses the music of a famous singer from West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Finally, other artists use an image or precise material culture: Chang Chi Chai and her research on the kites of Chinese origin in Brazil; Eric Fok and the colonial maps of Macao; Esvin Alarcón Lam and the commemorative arch made by the Chinese colony in Guatemala; Tromarama and the disappearance of a Dutch colonial building; and on one of the balconies of Osage, Shinpei Takeda and the floorplans of ships that brought Japanese immigrants to Latin America. His drawings are composed of the immigrants' logbooks and, over time, they will disappear from the surface of the Osage floor, just like any image will disappear in the course of history.

* microhistory - another series of artists seems more dedicated to the act of listening; their research is aimed at a one-to-one exchange and from there they reconstitute the memory of a person or a small community.[16] David Zink Yi films generations of Chinese who immigrated to Peru and who talk about the spices brought back and forth. To cook is to remember. Good example of this culinary transit is the performance by Shima, held at the opening. As an Okinawan immigrant family and owner of restaurants in Sao Paulo, cooking something "typically Japanese" is putting ingredients made in Brazil but catalogued so. Recipes go from generation to generation and the secrets need to be kept. Also, in the field of video, Fx Harsono runs a documentary on Indonesian Christian schools and the multiple layers of otherness - a Dutch teaching for supposedly Indonesian children, but who, like him, had Chinese ancestry. Miho Hagino and Taro Zorrilla have been conducting long research with immigrants and Japanese descendants in Mexico. How to express the feeling of missing a place by words? How to relate to a place never visited, when you are Nisei or Sansei? The video installation of Nguyen Trinh Thi - also based on an interview with a Vietnamese who immigrated to Hong Kong and opened a vinyl record store - could also be at that intersection.

* fictions of identity - finally, notions of identity and history can always be fictions. Our bodies enter and leave geographical spaces exerting different forces of attraction and repulsion, belonging and estrangement.[17] For some artists, therefore, more than affirming or recovering documental histories, it is important to follow in the field of fiction, confusion and lack of literality. Their works are more open to multiple readings and were essential in this project because of his polysemic character. It is necessary, I think, to still believe in the mystery of images. The literary text is essential for Juliana Kase and Sandra Nakamura. The first one makes a super8 film in Japan and inserts on the image a haikai poetry, while the second investigates the songs of the native peoples of the island of Hong Kong and projects them in the space like shadows.

The exploration of three-dimensionality as a place of estrangement is important for the other artists seen in these keywords. Daniel Lie and João Ó operate with organic materials and seen as traditional - the bamboo is folded in the case of the second and becomes masts in the case of the first in his occupation of one of the balconies of the Osage. When using a collection of fossils from Madagascar already present in the foundation, Lie cast a glance over the passage of time. On the other hand, Mimian Hsu, Mella Jaarsma, Jonas Arrabal and Kwok-Hin Tang use more industrial objects. Each sleigh bell used by Hsu is a reference to a day of disappearance of her grandfather in Taiwan; each newspaper that fills the clothes made with plastic cassava bags from Jaarsma's work is a reminder of the articles that bombard us about migratory flows. To look at the Japanese side of his family who always dealt with salt production in Brazil, Arrabal proposed an installation with water gathered in Hong Kong and watched its daily evaporation. Tang preferred to perform an act within his video installation where the colours of the flags of China and Hong Kong are echoed ghostly quickly. The carpet fixed to one of its bed structures says "welcome", but to what extent has this return to China been effectively welcomed by his generation?

These brief paragraphs and these approximations of these aspects of the exhibition’s works are patchworks - that is, they are a way of creating dialogues that are not at all inert. Several of the artists here invited can have their works read even by these four lines of force. It is an interpretive exercise that encompasses both my curatorial, critical and art historical practice, and especially the formation of my gaze as a public. Images escape our words; what would become of us if they were not greater than our attempts of verbalization? Just as I learned from this project that history is not everything, I am more and more sure that words, fortunately, are not everything too.

It is in my iconophily - not only mine, but of all contemporary visual cultures - that I find the desire and strength to continue thinking of new ways to enable ephemeral encounters between artists and images that unfold histories and stories towards the infinite. Because, as Chimamanda Adichie said in a conference, every story must be told, and we need many stories about the same places:

Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity. The American writer Alice Walker wrote this about her Southern relatives who had moved to the North. She introduced them to a book about the Southern life that they had left behind. ‘They sat around, reading the book themselves, listening to me read the book, and a kind of paradise was regained’. I would like to end with this thought: that when we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise.[18]

[1] “Indeed, in the parliamentary debate of 1857, concerning Chinese immigration, there was a revealing discussion of the impact of cultural constraints on the new population and labour policy. In the lower house, a deputy stated: 'When we sought to smash our civilization from African barbarism, [we are] going to colonize the Empire with the slothful Asian, a slave to routine and superstition.' Responding to the deputy, the Minister of the Empire, Couto Ferraz, the future viscount of Bom Retiro, explains the reasons that, in his view, made the Chinese less compromising: 'Chim does not leave his country, but with the purpose of acquiring some money , to form a small fortune, and always with the fixed idea and with the express condition of returning to their country after three, four or five years ... the government had never had the idea of wanting to increase the Brazilian population by similar way" in ALENCASTRO, Luiz Felipe de & RENAUX, Maria Luiza. “Caras e modos dos migrantes e imigrantes” in ALENCASTRO, Luiz Felipe (Org.). História da vida privada no Brasil – Império: a corte e a modernidade nacional. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1999, page 296.

[2] “First article: It is totally free the entry into the ports of the Republic of individuals who are valid and fit for work, who are not subject to the criminal action of their country, excepted the native of Asia or Africa, who may only be authorized by the admitted in accordance with the conditions then stipulated”. National Decree of June 28, 1890. The law was repealed two years later, in 1892.

[3] LESSER, Jeffrey. “A discontented diaspora: Japanese Brazilians and the meanings of ethnic militancy, 1960-1980”. Duke University Press, 2007.

[4] “Anyone who is in charge of writing the History of Brazil, a country that promises so much, should never lose sight of the elements that contributed to the development of man. But these elements are of a very diverse nature, and for the formation of man in particular there are three races, namely: the copper colour or American, the white or Caucasian, and finally the black or Ethiopian. From the encounter, the mixture, the mutual relations and changes of these three races, the present population was formed, whose history therefore has a very particular character. It may be said that each of the human races, according to its innate nature, competes according to the circumstances under which it lives and develops, a characteristic and historical movement. Therefore, seeing us a new people born and developing from the meeting and contact of so different human races, we can advance that its history should develop according to a particular law of the diagonal forces” in VON MARTIUS, Karl Friedrich Philipp. “Como se deve escrever a história do Brasil” in SCHWARCZ, Lilia & PEDROSA, Adriano (Org.). Histórias mestiças: antologia de textos. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2014, page 75.

[5] Due to the research for the X Mercosul Biennial I travelled in 2015 by Costa Rica, El Salvador and Guatemala (Central America); later I visited Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica and Panama (Caribbean).

[6] I would like to refer to some of the artists with whom I exchanged emails, visions and portfolios in preparation for this project. Unfortunately, their works could not be included in the exhibition due to scheduling, physical space or even dialogue with other works already selected. In any case, their works deserves reference and attention. Thanks to Iumi Kataoka and Maximiliano Matayoshi (Argentina); Ana Tomimori, Luciana Miyuki, Miguel Chikaoka and Yukie Horie (Brazil); Ignacio Wong (Chile); Erika Nakasone (Peru) and Yudi Yudoyoko (Uruguay).

[7] I am thinking, for example, about the exhibition “Olhar InComum: Japão revisitado” [“UnCommon look: Japan revisited”] curated by Michiko Okano at the Oscar Niemeyer Museum, in Curitiba, Brazil. The show had 21 artists and all of them came from Japanese families. On the other hand, most of their works didn’t have relations with any reflection about “Japanese culture” so the only criteria were their genealogy. Pointing to the same direction, we could also bold recent projects like “Transpacific borderlards: the art of Japanese diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City and São Paulo” at the Japanese American National Museum (2017); “Circles and circuits: history and the art of the Chinese Caribbean diaspora”, part 1 at California African American Museum and part 2 at the Chinese American Museum (2017); and “Relational undercurrents: contemporary art of the Caribbean archipelago” at the Museum of Latin American Art (2017). All these projects were funded by Getty Foundation and took part in the 2017’s edition of Pacific Standard Time.

[8] I would like to thank Alfredo & Isabel Aquilizan, Alfredo Esquillo, Gaston Damag, Jigger Cruz, Jose Legaspi, Jose Tence Ruiz, Lani Maestro, Martha Atienza, Pow Martinez, Riel Hilario, Stephanie Syjuco, Tatong Torres, Yason Banal (Philippines); Sin Tung Ho (Hong Kong); Bagus Pandega, Eku Nugroho, Handiwirman Saputra, Hestu Stu Legi, Irwan Ahmett, Jompet Kuswidananto, Jumaldi Alfi, Maharani Mancanagara, Reza Afisina (Indonesia); Alice Kok, Lai Sio Kit, Nick Tai, Peng Yun (Macau); Nge Lay (Myanmar); Lee Wen (Singapore); Tiffany Chung, Tran Luong (Vietnam).

[9] OSBORNE, Milton. Southeast Asia: an introductory history. Sidney: Allen & Unwin, 2016.

[10] MEDINA, Cuauhtemóc. “Sul, sul, sul, sul...” in IMHOFF, Aliocha & QUIRÓS, Kantura (Org.). Géoesthétique. Cleront Ferrand: ESCM, 2012, page 120.

[11] It is important to remember recent projects that are based in the same geopolitical concept. In Brazil, the biennial Videobrasil is the oldest one dedicated to the topic. Crated in 1983 as a festival, in 1991 it became an association and since them, biennially, it is the one of the biggest world events dedicated only to artists from the Global South, receiving artists from all continents. I would like also to quote “South as a state of mind”, a Greek magazine that before the opening of the last dOCUMENTA (2017), dedicated four editions to the art and culture related to the philosophical ideas of “South”.

[12] CAMUS, Albert. O óbvio e o obtuso. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 1995, page 18.

[13]HERNANDÉZ-NAVARRO, Miguel A. Materializar el pasado – el artista como historiador (benjaminiano). Murcia: Editorial Micromegas, 2012.

[14]FOSTER, Hal. “An archival impulse” in October. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004, pp. 3-22.

[15] FOSTER, Hal. Recoding – art, spectacle, cultural politics. New York: New Press, 1999. Aby Warburg’s concept of pathosformel and its use related to classical Western art can be helpful in this field of interpretation.

[16] The concept of “microhistory” was much developed by the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg in books like “The cheese and the worms: the cosmos of sixteenth century miller”, published for the first time in 1976.

[17] HALL, Stuart. Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1999.

[18] Conference by Chimamanda Adichie proffered at the TED Global 2009. This quote comes from the final two minutes of her talk.

(texto curatorial da exposição "The sun teaches that history is not everything", realizada na Osage Art Foundation, em Hong Kong, entre 25 de março e 06 de maio)